Boys, I'm Killed

The shots rang out at nearly the same time, the crowd watching agreed; one witness said he only heard one shot. Davis Tutt was the first to reach for his pistol as he faced James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok, but Hickok had the better aim. Tutt exclaimed "boys, I'm killed," after the bullet from Hickok's gun found his ribs. That gunfight in Springfield, Missouri marked the beginning of several legends, that of Wild Bill Hickok himself, and the gunfight duel itself as shown in the movies: enemies with guns facing each other in the middle of town.

Hickok's story retreated further into legend with the fictionalized TV show, "Wild Bill Hickok," which ran from 1951 through 1958.

Where's My Pa?

Grover Cleveland, during the presidential election of 1884, got his illegitimate child thrown in his face. His response to the scandal that followed went down in election lore because he won. He did not deny that the child was his. "Tell the Truth" was his tag line. But knowing "the truth" depends whether you believe the affidavit of the widow who said she was raped, or the stories in the press that had her consorting with multiple men, some of whom were friends of Cleveland. Some facts remain: that her son was taken from her and put into an orphanage, and Maria Halpin was briefly committed to Providence Insane Asylum.

Official versions of the story still exonerate Cleveland, telling his version of the story. Supporters responded to "Ma, Ma, Where's My Pa?" with “Gone to the White House, Ha, Ha, Ha!”

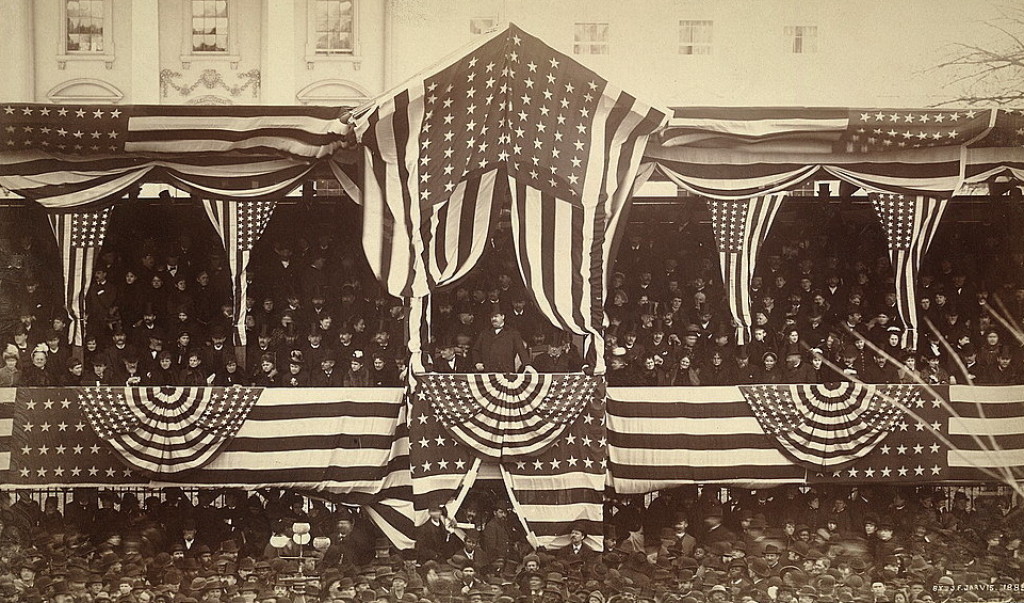

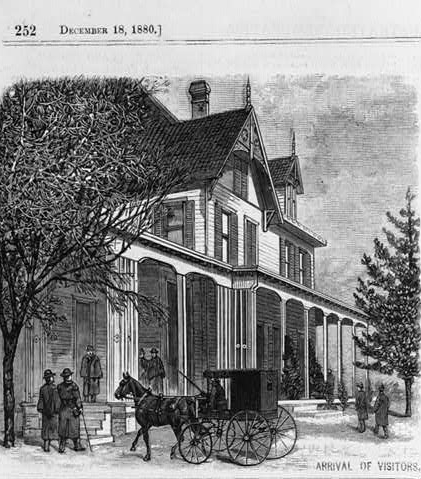

Stumping From the Front Yard

President Garfield had pioneered the technique of conducting a campaign for president from his front porch in 1880. It helped to have a home with access to a railroad stop built just for him. The tracks near his house brought the curious public to see him at a time when candidates generally did not campaign in person at all. William McKinley, who also had railroad tracks near his house, took the front porch technique into new territory in 1896 by recruiting friendly audiences. The last front porch campaign, by Warren Harding in 1920, controlled the message even more, befriending reporters by building them a press room and buying the reporters a car.

It was a far cry from the first folksy front porch campaign of Garfield, when reporters camped out on his lawn.

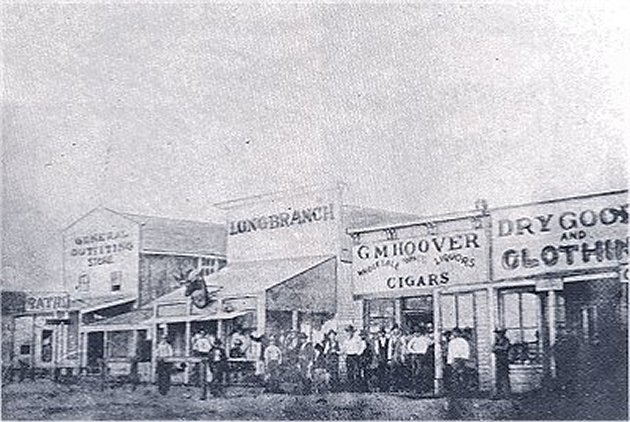

Bat's Last Gunfight

"Bat Masterson is said to be cool, decisive, and a bad man with a pistol." So the local paper declared when he was elected sheriff in Dodge City, Kansas during the wild west days of the late 1800s. His reputation as a killer was perhaps exaggerated, but it didn't hurt to be feared. He spent five years as a lawman, then lost an election. He left town, going back to his earlier occupation as a gambler, ending up in Tombstone, Arizona. He heard his brother was in trouble in Dodge and got on the next train. Back in town, he immediately challenged his brother's enemies. In the ensuing gunfight no one was killed, but Bat was fined $8 and told to leave town. He got out of Dodge the same night.

To "get out of Dodge" does refer to the wild Kansas town, but the phrase originated with the TV show Gunsmoke, set in that city.

Endurance, Fidelity, Intelligence

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog race has run since 1973 along the route that brought medicine from Anchorage to remote Nome when the city was in danger from a diptheria outbreak. Several Nome children had fallen ill with the contagious disease in the winter of 1925, and the only way to reach them was by a relay of dog teams. Balto, a Siberian Husky until then not considered particularly remarkable, led his team through a bitter cold blizzard to deliver the antitoxin on the final leg of the thousand-mile journey. Balto's feat stopped the outbreak and only five of the 1400 Nome residents died.

Balto's fame led to a life-size statue in New York's Central Park, the city's only monument to a dog.

Monument to the Railroad

The Bunker Hill monument in Boston, which commemorates an early battle of the Revolutionary War, also helped kick off the revolution in transportation that was the railroad age. In 1826, Gridley Bryant developed new technologies to move the big stone blocks for the monument. It would be one of the first attempts at rail transport in the United States, and some of Bryant's inventions are still in use.

This early railway was powered by horses, rather than locomotives.

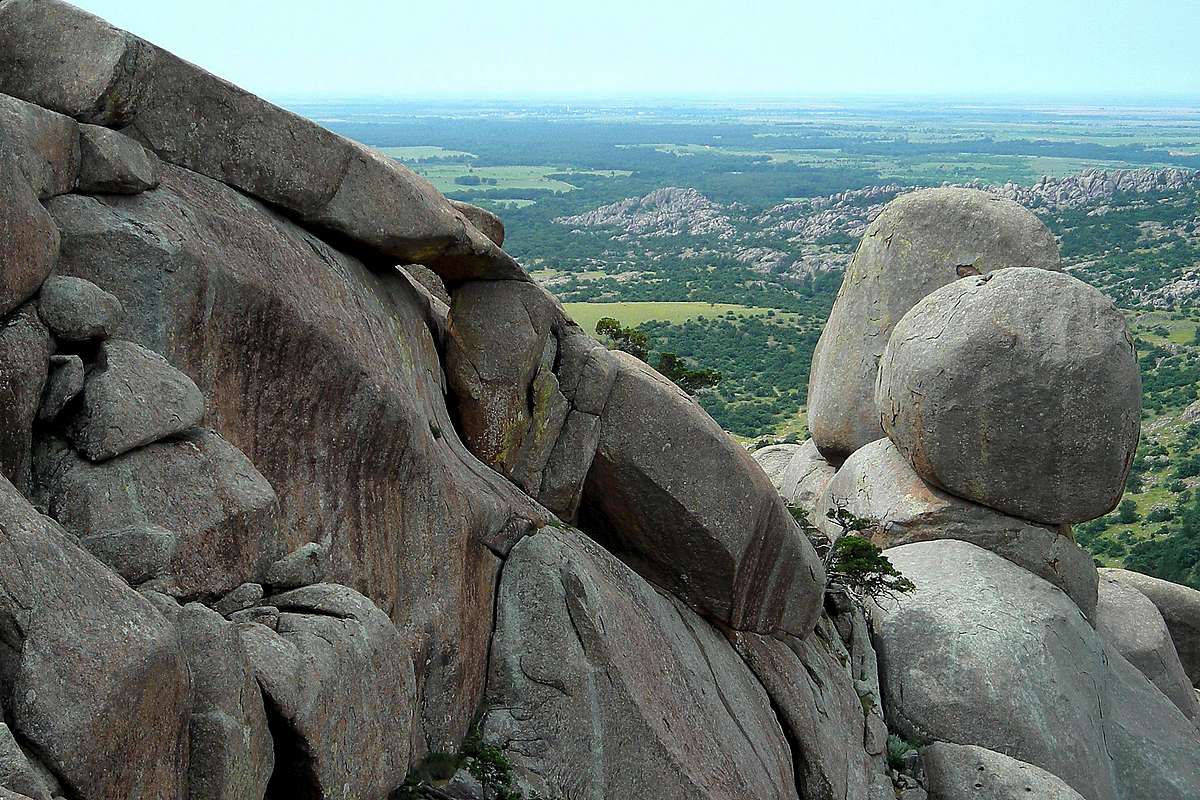

Geronimo's Bones

Feared and reviled for his violent resistance as his nomadic tribe was corralled onto reservations, Geronimo, an Apache warrior, was pursued between 1881 and 1886 and captured by the United States government. Although late in life he was allowed some freedom to earn money exhibiting himself at expositions and shows, when he died in 1909 he was still officially a prisoner of war at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and his grave is marked there. In 2009, the rumor that the Yale society Skull and Bones had stolen his skull in 1918 hit the headlines when his descendants sued to recover the remains.

Geronimo's bones may never have been buried at Fort Sill, with no skull to be stolen. According to a tale handed down from a member of the burial party, Geronimo had been laid to rest near Elk Mountain, Oklahoma.

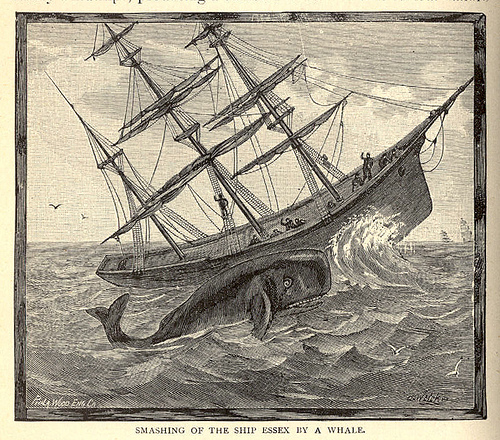

Revenge of the Whale

The hunting of whales was big business for a hundred years. In the late 1700s, an industry based on the oil of the massive animal began to grow in importance. Whales were hunted with ferocity for the huge profits whale oil brought as more lamps burned the smokeless fuel. But tales of the animals attacking back were not just fiction. The most famous was the attack on the Essex in 1820, which was the inspiration for Herman Melville's Moby Dick.

In 1851, the year Melville's masterpiece is published and panned, a whale attacked the Ann Alexander and sunk her.

The Spy Who Got Away With It

The secret of the first the atomic bomb developed by the United States during World War II was fiercely protected. Most of those caught passing on nuclear secrets were jailed and two were put to death. But one atomic spy evaded any consequences although he was known to authorities. He was left alone because the United States feared his prosecution would tip off the Soviets that they had cracked their coded communications, as that was the the only evidence against him. When the communications were declassified he was publicly identified as Theodore "Ted" Hall.

Hall worked on the Nagasaki weapon, a plutonium bomb, the same type that the Soviets detonated as their first nuclear test in 1949.

Phony as a Twe Dollar Bill

The Secret Service, whose job it is to find and destroy counterfeit money, doesn't go after the obvious fakes: they don't bother with novelty items like the twe dollar bill, which really exists, and will set you back $750 in legal tender. They were concerned, though, when they found a stash of billion dollar bills in West Hollywood. Unconcerned by a $200 bill with George W. Bush on the front, a clerk at a Dairy Queen in Danville, Kentucky gave out almost $198 in change.

Three dollar bills did exist, although they came to mean phony. The federal government of the United States has never printed a $3 bill, but the "United Colonies" did.